National Portrait Gallery, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

I generally prefer the written word to audiobooks. It was only when I listened to Shelby Foote's sui generis history of the American Civil War through Audible that I discovered that popular history does hold a special register when read out loud.

Over the past year or two, I have found immense enjoyment in listening through some of Dan Jones' histories, particularly what I would call his triptych consisting of The Plantagenets, Henry V, and The Wars of the Roses.

I call it a triptych rather than a trilogy because the very structure of the books is organized around its true centerpiece: Henry V.

I only chanced upon this format because I had listened through The Plantagenets and The Wars of the Roses side-by-side but was disappointed that while The Plantagenets ended with the accession of Henry IV Bolingbroke and The Wars of the Roses began with the surprisingly untimely death of Henry V, there was no portrait of that king upon whom Jones lavishes such praise.

That is of course until a mere week after I had finished the previous book and going upon Audible to find a new entry to pursue, I discovered that just two days before Henry V had been published, the latest in Jones' oeuvre and ready for the listening.

In his preface, Jones explains that he intentionally worked it out that he would start with The Plantagenets and come back to Henry V because he felt that his writing had not sufficiently matured and that he wanted the biography of this one monarch to be his biography par excellence.

I wish there were more authors so candid and disciplined about saving "the best for last", and I enjoyed learning more about the short life and reign of Henry V all the more for it. It is an artistic choice which places Henry V at the zenith of English monarchy before a decline from which the English and British royal pre-eminence would never truly recover.

My undergraduate years as well some years prior and hence were dedicated to the study of ancient and modern history, leaving one broad gap of that nebulous medieval period sitting in the midst of the Western narrative. (Of course I continue to endure embarrassing gaps in non-Western history that I can only hope to amend over a lifetime.)

Even my academic coursework that did enter into medieval history was far more topical than political, and for the longest time I failed to understand the face and figures of English monarchs that so many seem to recognize and know by heart.

Dan Jones is a kind tutor in that regard. He writes with an ease to the ear, helping you learn the fundamentals of English medieval history with a clear passion for the subject. As with great popular historical writing, he does not disguise which characters he favors and which ones disgust him, even if such opinions contradict conventional portraits of the wide cast who have sat the throne.

I release this today, October 25th, the six hundred and tenth anniversary of Agincourt to commemorate one of the most remarkable bloodlines in human history.

Nearly all know of William the Conqueror, Hastings, and 1066.

But far fewer know of the next great calamity in English history: the White Ship. Deep before the age of sail sat a magnificient sailing vessel off the coast of Normandy, still core to English holdings. Abroad were William Adelin, the heir to the reigning king Henry I, and wide swathes of the young English nobility. It was a festive gathering with feasting and drinking as the ship prepared to cross the English Channel, that small isthmus that separated nations.

Its captain was none other than Thomas FitzStephen, the famous captain who served William the Conqueror himself, and it was to be an auspicious occasion for an extremely routine crossing. That is until the boat, departing in the dark, struck a submerged rock and began to sink. In drunken chaos and confusion, all drowned and perished, save a butcher who lived to tell the tale.

Medieval history contains a dramatic array of these stories which would be unthinkable today. The sheer contingency of such a thing that would overturn history itself.

There was no other heir to the English throne, Henry I had his barons swear fealty to his daughter Matilda, but upon his death, few of them felt interested in upholding her as their new queen and sovereign.

England descended into a deep, dark period of Anarchy and civil war whose ravages it would not see again until the Wars of the Roses three hundred years later. Ironically, Stephen of Blois who claimed and subsequently acceded to the throne, had been aboard the ship but disembarked before its departure as he was too drunk.

Matilda fled but having married the Holy Roman Emperor became known as the Empress Matilda and dramatic in-fighting occurred as she and Stephen of Blois fought over the throne. Through her husband Geoffrey of Anjou, she launched a bid to reclaim the throne and after many contentious episodes and even a decisive victory at the Battle of Lincoln she was forced to forfeit her bid and left the charge to her son Henry II.

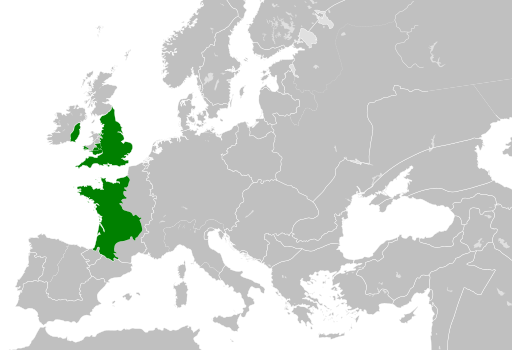

After further fighting, Henry II did in fact win the claim and subsequently the English throne in 1154 alongside all his fathers holdings, forming not only the Angevin Empire of vast territorial breadth but also the Plantgenet dynasty that would rule England until its ultimate demise in the Wars of the Roses with the fall of Richard III in 1485.

Henry II's domain was truly massive.

Map of the Angevin Empire in 1190. Source: Wikimedia Commons - CC BY-SA 4.0

But it didn't start that way.

This was due to one of the most remarkable women of Medieval Europe: Eleanor of Aquitane.

Eleanor had inherited the equally sizable and wealthy Duchy of Aquitane at the age of thirteen, and within the same year married the Capetian Louis VII, king of France.

In the fifteen years of their marriage, Eleanor provided Louis with two daughters, and not a single male heir. Aside from other marital tensions, the geopolitical risk of inheritance led to even more fractious relations within their marriage.

In 1152, Louis and Eleanor arranged for their marriage to be annulled on the grounds of consanguinity (too closely related). The daughters would go with Louis, but Eleanor would keep her lands and go her own way.

Within eight weeks of this annulment however, Eleanor had found a new husband in Henry II who at this time was still not yet king of England. However this was quite the snub to Louis, one of many that hearkened the Anglo-French rivalry that would last until the nineteethn century.

This not only meant that all the lands of Aquitaine would fall under English suzerainty (alongside Normandy) once Henry II acceded to the throne, but other continental territories such as Poitiers would fall under this Angevin sphere which encircled Capetian holdings more than any ruler could have hoped for. Henry II would end up ruling more of modern day France than the French king did.

The irony of this was that Henry II and Eleanor were more closely related than she was to Louis VII, and this had been the grounds to nullify their marriage.

What was even more insulting to Louis VII is that within the first year of her remarriage, Eleanor gave birth to a son William and would go on to produce four more sons and several daughters in the same length of time as she only gave birth to two daughters for Louis himself, making it seem to observers as if the fault of infertility lay with him. It was only in his third marriage that Louis VII would father a male heir in 1165, the year before Eleanor would provide her last son John to the Plantagenet dynasty.

It would turn out that Henry and Eleanor would share a rancorous, passionate marriage, perhaps equally eventful to his reign in general.

Henry II is remembered today for being exceptionally ruthless and energetic, always on the move in his expansive territories. He made remarkable and groundbreaking reforms in governmental administration, law, and royal finance that would pave the way for an exceptionally strong kingdom.

Yet in spite of all this, his stubborn personality cost him dearly.

His association with the murder of the Archbishop, and his former friend Thomas Becket would haunt him the years of his life and his legacy ever since.

The revolt of his son "Young Henry" in his later years would also stain his legacy, though it is remarkable he could put down a coalition assembled by his wife and children against him.

Henry II is one of those seemingly omnicompetent rulers whose own effectiveness, particularly the personality traits that made them so effective, were the cause of their own downfall.

Jones argues it is not clear if Henry II had designed for his entire realm to continue under a single Plantagenet king following his death, but it did surprisingly remain more or less united through the reign of his son Richard I until the military foibles of John I.

Richard I receives a warm reception in Jones' telling as the warrior statesman he is often revered for in legend. More French than English, Richard is depicted as the only capable general to challenge Saladin in the Third Crusade, gaining the admiration of that equally remarkable sultan.

All the same, he was not nearly the same administrator as his father and largely abandoned the care of the realm to others, exhausting the financial stockpiles of his father on military adventure, one of which would prematurely cost him his life in a campaign against Philip Augustus of France, one in which he decisively reconquered many of the Norman holdings usurped by the Capetians.

The crown now acceded to King John I, a notorious blot on Plantagenet pride, but a monarch who enjoys some level of rehabilitation in Jones' narrative.

John is often associated with cruelty and cowardice, such as in the tales of Robin Hood, but in point of fact Jones contends that John inherited the administrative capabilities of his father, though the degree to which he extracted revenue for royal purposes, would be part of his downfall.

He made the royal treasury richer than it had even been under Henry II, but the tragedy of his royal tenure is the catastrophe that befell his own military campaign as he sought to re-emulate his brother Richard in the recapture of French territories.

The other shoe had dropped in the Plantagenet and Capetian rivalry, and Philip Augustus through no lack of ingenuity on his own part outwitted John and kicked the Plantegenets straight out of Normandy, not to return until the Hundred Years War a century later (and even then only temporarily).

The campaign led to a crisis of legitimacy which led to a baronial revolt and an even more embarrassing military loss at home that would lead to the Magna Carta of 1215, the most famous document from Plantagenet rule.

He would not be able to pass his days in ignominy either as during the continuation of this conflict, John would die of an illness, leaving the crown to his nine year old son Henry III.

This was the first time of extended regency for Plantagenet England, and upon his accession, Henry III had half of his realm in rebel hands. Through the capable hands of ministers like Cardinal Guala and William Marshal, however the child king would have his realm restored and peace as well with a France which may have been considering a cross-channel invasion.

Henry III had an exceptionally long reign, fifty-six years, the longest of medieval Europe, and the fourth longest of all English monarchs.

Unfortunately, he had inherited the luck of his father. His long awaited campaign to reconquer French territories availed itself in disaster. He had to deal with his own revolts but left the core Plantagenet holdings intact when he passed the crown on to his son Edward I.

Edward was an unusual name in this period, but it was selected by Henry III who had a deep fascination with England's Anglo-Saxon history, particularly Edward the Confessor who lived a mere generation before the Norman conquest.

And as what may have come as a surprise to many, Edward I would revitalize the Plantagenet dynasty as a warrior king "Longshanks" with exceptional military activity, starting in his prince years when he escaped a hostage situation during a baron's revolt and then defeat those barons in the Battle of Evesham, before departing on the Ninth Crusade. It was during this venture abroad that he inherited the crown.

A tall, intimidating man, Edward notably took great efforts to reform his royal government, especially the common law which had long lay unattended since the days of his grandfather King John.

His reign was one of restoration for the Plantagenet crown.

The first was Wales. A quasi-sovereign state since the initial incursions by the Normans under William the Conqueror, Wales had risen up on several occasions to increase its autonomy or locally held fiefdom. Edward I would crush the Welsh a first time, and then a second time which marked the royal conquest of Welsh lands. Wales would be a royal fiefdom, hence the title "Prince of Wales".

But that was not all, for Edward I would come to be known as the Hammer of the Scots.

The Scottish throne existed alongside the English throne, the two generally minding their own business up until this point. In the 1290s, King Alexander III of Scotland died triggering a succession crisis. Edward used the opportunity to advance himself as an interregnal figure, against the protests of local lords. Edward's pretensions were generally tolerated though until he attempted to enlist Scottish levies against France as if he were the King of Scotland. This alongside other points of friction caused a war between England and Scotland to erupt, Scotland allying with France who was attempting to conquer Gascony from the Plantagenet throne at the same time.

Despite the Scots taking initiative in launching their attack, Edward I quickly and decisively reversed the Scottish offensive and then invaded Scotland in March 1296, besieging castles in blitz succession, and subjugating most of the kingdom by July. Scotland's first subjuation under English suzerainty would formally last thirty-two years until the Treaty of Edinburgh-Northampton restored it.

Aside from this, Edward I had to face the French as well, in alternating years with the Scots. Norman pirates had been plaguing the coast, and using this pretext, Philip the Handsome had confiscated the traditional English territory of Gascony in southwestern France, only for Edward to engineer a massive coalition to attack Capetian France from all sides. This was to some degree successful even though the German king (one of the few who could not be called Holy Roman Emperor because the pope never crowned him) backed out at the last minute.

From this conflict, Edward negotiated marriage of his son to Philip's daughter Isabella as well as the retrieval of his French lands.

What started as a skirmish with pirates turned into a ticking time bomb. For this marriage between England and France would birth the casus belli of the Hundred Years War which would cement Anglo-French enmity for centuries after. But more on that soon.

Following two lame duck kings, Edward I had made a marvel of his administration in turning English fortunes toward propserity, starting his career as he did as a hostage of a disgruntled noble against his impotent father.

And yet as with Platagenet succession, or English succession (or even monarchic succession on the whole), a vigorous, robust king can very easily be succeeded by an incredibly decreipt one.

Such was the case for Edward I whose thirty-five year reign ended in 1307, and the one to take the crown was a fourth son who probably had never accepted to wear the crown himself.

This twenty year reign was marked not by success but failure and controversy. Edward II was eccentric. Most notorious for his perhaps homosexual fixation with Piers Gaveston to whom he bestowed incredible powers (and Gaveston with minimal propriety certainly flaunted this coat of many colors), or the Despenser family whose pretensions to power using the friendship of the king sparked a violent conflict with the Lancasters. The Lancasters, led by Edward's cousin, had been so fed up with the situation they captured and killed Piers Gaveston for his impudence, sneding the king into a perennial sulk.

As this unfolded, Scotland broke free of English rule at the humiliating Battle of Bannockburn, and Edward seeking peace with France, sent his French princess wife Isabella back to France to negotiate, only for her to defect against him.

What comes next is another colorful episode in English royal history as Isabella, aligned with her lover Roger Mortimer, launched an invasion of England and captured the throne, forcing Edward II to abdicate and die in ignominy.

Things could have devolved even further under the unpopular corruption and tyranny of Mortimer who reigned de facto as regent alongside Isabella while Edward III came of age. If Edward were a Henry III or even like his father Edward II, he would have lived his career a mere puppet of the Queen Dowager.

But Edward III was more of the stock of his grandfather Edward I. For like Edward I who was kidnapped by a rebellious lord only to overthrow that revolt and definitively assert his own dominance, Edward III was no less a contender on this front. At the age of seventeen, he executed a precarious yet cleverly planned coup d'etat against his mother and Roger Mortimer, claiming the throne for himself.

From there, he quickly mounted a highly successful invasion of Scotland, against popular opinion, secured a victory, and annexed many border territories. Extricating himself from Scottish politics, Edward III had set his sights on a far larger, more glorious prize: the French throne.

Philip the Handsome had died in 1314. So too had his son Louis X in 1316. The unborn son of Louis X was set to become king, but John I lived only five days, as long as his reign did. From John I, the French crown reverted to Louis X's younger brother Philip V who died within six years with no male heir. His younger brother Charles IV then took the throne but also died within a few years with no male heir.

By certain succession terms (including those practised by earlier Capetian's), Edward III, as son of Isabella, grandson of Philip the Handome, and nephew of all these previous kings, had the most direct claim to the throne. However submitting the throne to an English monarch and the traditional Plantagenet enemy did not sit well with the French court. They contended that a man could not inherit the throne who his mother's line, and so they picked the son of Philip the Handsome's younger brother instead. They inaugurated a new Capetian dynastic branch, the Valois, who would rule under Philip VI.

Depending on geopolitical circumstances, this was a legitimate choice, but Edward III was a young man, fresh off the heels of victory against the Scots, and looking to carve out a legacy for himself.

To do this, Edward III completely overhauled the fragmented nobility structure at home in England. He had seen the centuries of problems the barons had caused for his predecessors and devised a solution to structurally prevent another baron's revolt from occurring. Edward III created six new earldoms, higher-ranking intermediates who would interface with the lower ranking barons and thus provide a containment strategy for unrest among the lower nobility. He was also extremely generous with new titles of lower nobility as well, providing pathways to power and success, which many craved and no longer needed to pry from existing hands. Surprisingly enough, this entire re-engineered aristocracy was rather popular as ambitious nobles could set their sights on earldoms rather than feeling the need to target the throne itself for influence or power.

Of course this masterful political engineering, while it would emphatically dissolve any risk of national baronial revolt against the king, greatly enhanced the power and prestige of individual Earls, leading to a new, more confederated power structure which would come to full friction and enmity with the War of the Roses within a century.

But for now, Edward III had created an entirely new incentive structure for the ambitious that would dovetail neatly with a War in France where plunder and glory await.

His inital forays into French affairs met mixed results, but in 1346, Edward landed an army in Normandy, decisively crushed French forces at Crecy, though outnumbered two-to-one, and then lay siege to the coastal fortress of Calais which fell into English hands on 1347, never to be pried definitively from them until 1558 under Henry VIII, a century after the Hundred Years War had ended.

Renown was won by Edward, his nobles, and his son Edward the Black Prince. This was the greatest armed conflict on French soil since Richard I, and the English were sweeping up territory after territory.

Despite this, Edward III was arguably not the greatest administrator or strategist.

He was a massive spender who enjoyed the finer things, including feasts and putting on the general performance of medieval monarchy in full flair. He spent exorbitant sums on allies or other miltary ventures, even if their returns were less than favorable, trusting that the conflict in France would yield dividends that justified every expense.

Yet the expenses outraced the results, and levied taxes at home produced resentment and strain on economy and popular mood. Grumbling at foreign wars would begin to incubate even if the glorious prestige of Edward III would nullify threats of uprising. Edward meanwhile simply could not find it in himself to rule and govern his own realm, he was much too interested in the thrill of adventure, that he found in France in his earlier years, even as he grew old and weak, and the war entered a standstill.

Edward the Black Prince who had died prematurely became a nostalgic beacon of the war's glorious early years, even as Edward III lay dying in 1377.

It was the Black Prince's son Richard II who would inherit the throne. Though guided by the magisterial, able hands of his uncles (Edward III's other sons) like John of Gaunt, Richard II would come to be known as one of the worst kings in English history.

Though he showed a promising start in personall standing down a mob at age fourteen during the Peasants Revolt of 1381, a long overdue conflict from his grandfather's oppressive taxation practices, Richard II would become the embodiment of cruelty and tyranny. While King John's cruelty was offset with his capable efforts in legal and administrative reforms, there was nothing redemptive in Richard II outside his patronage of the arts (including Geoffrey Chaucer).

Throwing away a peace treaty with France that would have recognized a significant expansion of England's ante bellum French territories, Richard played for a truce and a marriage with the French king's daughter who was six years old, twenty three years younger than him.

Those who had criticized his early reign or offended him during his regency soon came to pay the price as Richard undertook arrests or exile of various members of the nobility, without a clear strategic reason for the agitation of various members of the nobility, outside personal slight. A great circus court ritual was set up to humiliate various nobles and the Archbishop of Canterbury, all while proffering pardons of clemency for the invented misdeeds. Many had their lands stripped and given to those who flattered the king.

John Gaunt's son Henry Bolingbroke who was a childhood friend of Richard II was the most noteworthy victim of such malfeasance as his exile would germinate the first deposition of a Plantagenet king in favor of a new lineage. Henry Bolingbroke had all his lands stripped from him and he was left to reside as an exile in Paris where Richard II felt the French would keep him safely hostage there out of a desire to protect the peace.

This was an incredible miscalculation.

For in 1399, Louis I established control over French government, and seeing the truce with England as an obstacle to reclaiming territory, Louis let Henry Bolingbroke lead an armed invasion of England. Richard II was in Ireland at this moment, along with his small coterie of loyal officers. His unpopularity was so overwhelming that England quickly gave itself to the usurper, and no armed battle took place. Richard II merely surrendered and lived out the rest of his years in a dungeon.

This of course was a tricky succession maneouvre. Plantagenet succession followed clearly established laws since Henry I's accession three centuries ago. There had never been a disruption like France had most recently faced in the extinction of the Capetian primary line.

Richard II was the legitimate holder of the throne as son of Edward the Black Prince. Henry Bolingbroke (now Henry IV) was son of John of Gaunt, and Edmund Mortimer sat closer to the inheritance than Henry IV did. When Edward II had been deposed it was ostensibly in order to put his son Edward III in charge. This was a clear rerouting of the line of succession.

Mortimer would himself later rise up in rebellion against Henry IV, but even more critically one could argue that this deposition here was the spark behind the War of the Roses which would emerge following Henry V's death. The gunpowder was Edward III's reorganization of the realm, and here was the lighting of the match that would only go off in a certain matter of time.

Henry IV though not a bad king himself, according to Jones, was forever haunted by his deposition. Domestic strife at home would rear its head every so often including dopplegangers pretending they were Richard II, even after he had ostensibly died. Henry IV would grow sickly and paranoid even as he consolidated his hold on the throne, haunted by guilt over what he had done, even if many understood the necessity of such an usurpation to protect England from Richard II's dismemberment of the realm.

It is in this ambivalent twilight that Dan Jones' The Plantagenets ends. There is something autumnal and murky with how the primary line is extinguished through usurpation and blood feud, but there is a dawn-like spark that will emerge with the next volume.

Henry V is the centerpiece of Jones' Plantagenet lore. The wunderkind, the omnicompetent king who would be the greatest to wear the crown of Westminster.

A man who came incredibly close to not becoming king at all. For at the age of 16, the young prince Henry joined his father at the battle of Shrewbury in 1403 where he earned an arrow embedded within his left cheekbone.

Grown men had died from far more tangential wounds and yet Henry would survive through the aid of the royal surgeon John Bradmore.

From there his star would only continue to rise.

While mere prince, Henry would subdue the entire Kingdom of Wales which had risen up in revolt yet again. Wales had risen up in revolt against their English overlords time and again for centuries at this point, but after Henry's forceful strike, Wales would never rise up again.

By 1410, with his father ailing, Henry V had gained virtual control of the English government, at the age of twenty-four. He would accede to the throne upon his father's death three years later.

Henry V marked the watershed moment of the vernacular English language which for the first time became the language of government record. He was a patron of the arts, well versed in philosophy and literature.

And most notably he was not averse to the ways of war.

Henry V nearly immediately set himself up for the task of renewing a claim to the throne of France, a claim that had wasted away through the internal dissension of the past generation.

None would ever come closer to such a foothold than Henry V.

While Henry II had through marvelous fortune and luck inherited massive feafdoms that formed the Angevin Empire, Henry V was prepared to fight tooth and nail to restore the claim of such a heritage, and beyond.

Henry V sent exorbitant demands to the French as conditions of peace, clearly with the intent to spark conflict anew. The French promptly rejected Henry's terms, and Henry prepared for a campaign to take France.

It must be remembered that Normandy had been formally lost to the English since the days of King John. England possessed Calais and Bordeaux but much of its continental holdings had been steadily siphoned by Capetian incursions.

Launching a naval invasion in 1415, Henry besieged Harfleur in Normandy which fell a month later.

The French had invested this time in mobilizing their forces, compiling the cream of the chivalric crop to repel the English invaders.

As Henry V marched from Agincourt, defying his councillors frantic warnings, he met the French armed forces at Agincourt on the 25th of October, 1415.

The odds were not favorable for the English.

English forces composed primarily of longbowmen were set against a near equal number of French archers who in addition to this had double that figure in infantry and calvary.

The French were prepared to swarm the English line, but through fatal strategic and tactical errors (i.e. the infamous frontal assault) the French were entirely slaughtered in one of the most lop sided victories of military history by a force outnumbered over two to one.

This victory cemented Henry V's drive toward Paris and reconquest of Normandy. By 1419, much of northern France now lay in Plantagenet hands. The French royal family who had split into a dynastic struggle between Armagnacs and Burgundians failed to unify against the English threat.

With the threat of total collapse for French sovereignty, both Armagnac and Burgundians agreed to negotiations for a truce. When the Duke of Burgundy, John the Fearless, sallied forth to meet his Armagnac counterparts, he was tricked under these false pretense of negotation and promptly assassinated.

This egregious violation of diplomatic norms sent the Burgundian faction reeling into English arms, negotiating that they would submit to Henry as their sovereign if he would sufficiently punish the Armagnacs for their crimes.

It was only a matter of time before Henry V marched into Paris where the impotent King Charles VI lay waiting, with no recourse. Henry V arranged to marry the daughter of the French king and the Treaty of Troyes which guaranteed that Henry V and his heirs would inherit the throne of France, wresting inheritance claims from the Dauphin who had retreated south to central France.

Through immense energetic ruthlessness, strategic planning, and tactical genius, Henry V had decisively reversed a dead claim, recaptured traditional English holdings, and extended his claim to the entire Capetian throne. All in the space of five years.

However, God was not to ordain the fruition of such plans. For though Henry V shortly thereafter begot his heir Henry VI, his brother Thomas would blunder the military situation in France in 1421.

Henry sailed from England yet again to fix the situation, and captured Meaux in a decisive siege. It was however at this siege that Henry V would fall ill from dysentery or some illness. One from which he would only deteriorate, before dying in France at the age of thirty-five. His son not even old enough to speak.

A reign of less than ten years had done more to favorably change England's fortunes than many monarchs who lived full lifetimes. Thus this shortest volume of Dan Jones' triptych comes to a close.

However, there is one thing worth noting from this conclusion. A very poignant footnote in history.

Jones, in summarizing the life and reign of Henry V, recalls Henry's declarations that he had been sent by God as a scourge to France and the Capetians for their sins.

If anyone had read Dan Jones book on the Templar Knights, they will recall how that order had unceremoniously collapsed.

The Templars who had functioned originally as a crusading military order had come to be entrusted as a banking agency by many of Europe's monarchs and nobility, given their charter and their international status which gave them geopolitical independence and military force of arms to protect their holdings.

The French King Philip the Handsome, in need of quick cash, had cast his eye on Templar assets. Through conniving with the Avignon pope, they manufactured charges of sexual crimes such as pedophilia and many other blasphemous acts, which Jones believes were nearly universally false.

On such trumped up charges, French royal forces stormed all Templar holdings within reach, plundering them, and capturing the surrendered knights and monks who were promptly tortured to evoke confessions of their misdeeds.

Grand Master Jacques de Molay was a focal point of months and years of torture. He was an old man in his sixties but a sturdy soldier who had committed his entire life in military service for Christ and was deeply committed to the Christian reconquest of Jerusalem.

After a protacted amount of time, he agreed to sign a letter of confession with him own hand, to disown the blasphemous activities of his order.

However, de Molay soon retracted this confession and no amount of French torture could break his resolve a second time.

On March 18th, 1314, de Molay was taken to an island where he was to be burned at the stake, the executors taking special care to ensure he would burn slowly and painfully.

As the flames licked the flesh of the old man who had dedicated his entire life to serving the mission of God, his voice allegedly rang out from the flames.

He pronounced with a clear conscience that God would exonerate the Templars for these false accusations, and that the French king and Pope who engineered the destruction of the Templar order, an order that had saved an earlier Capetian king from death in the Crusades, an order humiliated and condemned purely for the sake of expropriating their assets, that these two men would suffer God's curse for what they had done.

Within a year of this date, both Pope and King Philip would die at a premature age.

The House of Capet which had ruled France since 987 would fail to produce any male heirs after this date. The primary Capetian line would die out in 1328.

King Edward III would invoke his claim from this dynastic event to trigger the beginning of the Hundred Years War which would plague France for over a century.

Henry V, the scourge of God, would humiliate French military might and political prestige again and again.

Who can claim to know the ways of God, but one cannot discount the curse of Jacques de Molay and the troubles which would embroil France for so many years.

Plantagenet England had reached its apex under Henry V.

The third volume concerning the War of the Roses marks the downfall of the Plantagenets as they disintegrate in a bloody, ruthless conflict that would mark the end of medieval England, and the dynasty that had ruled England since the Anarchy three centuries earlier.

Edward III had establish power giants through the creation of earldoms.

Henry IV had unsteadied the line of succession through his usurpation of the throne.

Henry V through sheer force and determination had legitimized his claim to the throne but had lived far too short a time for the realm to forget the history of the usurpation. The Bolingbroke claim was not certain.

And so we come to Henry VI, perhaps one of the most unfortunate monarchs to ever sit the English throne.

Acquiring the thrones of both England and France just shy of his first year, in the midst of grand conflict with the Armagnac French who still maintained a strong foothold in French territory, and a member of a still new cadet Lancastrian branch of the Plantagenet dynasty, Henry VI had some of the highest expectations ever laden on a newly minted King of England.

By Dan Jones' telling though, Henry VI was born into equally fortunate circumstances that few young kings did not have, a Regency Council committed to the legitimacy of their sovereign and the interim stewardship of the realm. Henry V had been blessed with brothers who were for the most part equally capable and loyal, and these uncles of Henry VI would guarantee his claim to the throne while he grew up.

Of course, this did not belie the importance of a royal mythology that needed to be erected around this young sovereign. That he was a wunderkind of sorts who showed preternatural abilities to command the English throne. Jones includes an amusing example of this where the two year old king had apparently written and signed a remarkably elegant letter of his uncle commending him for his good abilities and charging him with further military action in the realm of France.

Tenuous pagentry aside, there was a genuine commitment to preserving the king's autonomy, a dedication that was tested when Henry V's youngest brother the Duke of Gloucester attempted to name himself Lord Protector and was soundly rebuffed. He would be a thorn in the Lancastrian side for decades to come.

Yet the English war cause suffered reverse after reverse as time elapsed and the king slowly came of age.

Already the remarkable Duke of Clarence, brother of Henry V, was killed by Scottish soldiers in France before Henry V passed.

The Earl of Salisbury, deemed the most effective English military commander was struck by a cannonball at the Siege of Orleans and died an excruciating death thereafter. Joan of Arc emerged and arrived at Orleans, lifting the morale of French forces who forced the English to withdraw. John Talbot, an equally ferocious English command, was taken prisoner mere months later.

Even as military efforts faltered, the Regency Council was divided on the diplomatic angle of handling the conflict. Some wanted to continue the war, Henry V's brothers were sympathetic to peace but disagreed on the terms to settle for. Most seemed resigned to forfeiting the claim to the French crown that Henry V had snatched up a mere decade before.

The death of King Charles VI whose bouts of mental illness and insanity had left the French crown headless and fractured among its own regency council further accelerated the French revival as his son Charles VII, though excluded from Paris, was an able military and political commander who steadily worked his way to reclaiming everything his father had lost.

An attempt at peace between the English, Armagnac, and Burgundian factions completely backfired for the English when their Burgundian ally switched sides to the Armagnacs and denied English sovereignty over the crown.

At home, matters grew more fraught as the young king slowly grew up and gave more and more indications that he did not quite resembles his father in mind, spirit, or body. In fact he bore some resemblance to his mother's father Charles VI instead, the very king who had failed to exercise even the slightest leadership in defending his throne against Henry V.

Nothing of war or politics seemed to interest Henry VI, he was timid and most interested in intellectual matters and questions of piety.

Even as he graduated from minority, it became clear to all close enough to see, that the machinery of regency would need to live on, perhaps indefinitely.

What was more, Henry VI's mother, Catherine of Valois, had been widowed during her pregnancy when she was only twenty years old. Of course it is a political problem when a young Queen Dowager is eligible for a husband. What claims or gambles for power could occur through her new husband. As marriage deals were discussed, Catherine herself entered an affair with a Welshman Owen Tudor, a mere servant of the queen. This was astounding for the Welsh were treated with great approbation, and English law explicitly curtailed the rights of the Welsh in civil and criminal matters. When Catherine became pregnant by Owen, a special Parliamentary law was passed to grant Owen the status of an Englishmen. The couple were whisked away from political affairs whereupon they would have six children together.

Henry's advisors attempted to negotiate a marriage between him and the daughter of Charles VII who naturally flatly refused as his grip on the French crown was only improving. Instead he was paired with Margaret of Anjou, a more distant Valois relative who would in turn become a formidable actress in English politics and affairs, far more than her husband the king.

In this time though, many of these regents and advisors themselves aged out of the situation, leaving a power vacuum that was steadily and meticulously consolidated by the Earl of Suffolk who sought diplomatic peace in France before all was lost. He was opposed by the king's uncle that racuous Duke of Gloucester, and Gloucester's friend and ascending ally, the Duke of York.

Suffolk had been the one to arrange Henry's marriage and was a prime orchestrator of all royal affairs by this point in time.

But things grew tense.

And as they always do, they began to unfurl, in a surprising way.

Gloucester's wife Eleanor was a controversial figure. In part because she was a second wife. Gloucester had previously been married to Jacqueline of Hainaut which had landed him some political connections with Philip the Good of Burgundy (who at the time was still England's ally). However he took up Eleanor as his mistress while he was still married to Jacqueline. He had fallen so in love with her that he engineered character assassination against his first wife in order to secure a marriage annulment so that he could wed his lover. Such scandal was not unknown to Gloucester, but as Jones reports since she was a relatively honorable and pious woman, this was a rather sordid move. And as a countess of lands neighboring Burgundy, perhaps not immaterial in Philip the Good's decision to switch to the French side a year or two later.

However that is not the trigger of the English crisis.

This second wife Eleanor enjoyed her astrology and flirtation with the dark arts. It was reported that upon consulting two astrologers they had predicted for her the day when King Henry VI would die. Not unimportant considering her husband would be a contender for the throne if Henry VI would die without an heir.

News of this quickly spread, and those who were already not fond of Gloucester's fecklessness and loose cannon bids for power jumped at the opportunity. Eleanor was tried for treasonous sorcery and sentenced to life in prison while her astrologers were imprisoned and executed. Gloucester himself was sufficiently humiliated he was compelled to retire from public life.

This ceded power to Suffolk who thereupon negotiated a secret yet somewhat humiliating temporary peace with France, one that Henry was firmly in favor of, but would not reflect well upon Suffolk's capabilities.

Things continued to deteriorate as Suffolk managed to amass charges to arrest Gloucester for treason and attempt to scapegoat the war failure upon him. However Gloucester died while awaiting trial, removing one more royal player from the game.

As the peace effort failed and England continued to flounder in France, this triggered what could be called a vote of no confidence by England's nobility who arrested Suffolk and attempted to execute him for treason. Henry intervened to reduce this to a temporary exile in Calais. In spite of this, Suffolk was assassinated en route before he even reached his destination.

As is very common with the broiling Wars of the Roses, characters enter and exit in quick succession as they die off, and so with Gloucester and Suffolk erased from the picture, the Duke of Somerset would succeed Suffolk as the leading voice of the peace faction.

Somerset forged an alliance with Queen Margaret who herself had King Henry VI wrapped around her finger and the two of them commandeered the authority of the throne to advance their cause.

By the 1450s, England lost Normandy to France, this time forever. Evolving feuds among the nobility were starting to erupt in armed skirmishes and violence. Henry VI bungled attempts to bring the various sides together, further undermining trust in the crown as a mediating authority.

When news of Gascony's fall to the French arrived, traditionally rich Plantagenet holdings that had never even belonged to Capetian France, but to Eleanor of Aquitaine, Henry VI suffered a mental breakdown. At this point, the Hundred Years War was effectively over. In this moment of crisis, Richard of York asserted himself as the Lord Protector of a new Regency Council in 1454.

The Duke of York was perhaps the strongest member of English nobility. His holdings and military retinue exceeded that of the Lancastrian king himself. His claim to the throne was also stronger than Henry VI's if one went all the way back to Edward III. He was a force to be reckoned with and had no misgivings about edging out Queen Margaret from the regency when she attempted to claim it.

Furthermore, from the background, Queen Dowager Catherine (Henry V's widow) had died, but her two sons Edmund and Jasper Tudor were introduced in English power politics as players. Their half-brother Henry VI granted them many gifts and favors, and they ended up throwing their cause in with Richard of York.

York quickly imprisoned his arch rival Somerset, but before he could further consolidate his power, Henry VI recovered from his mental breakdown within a year, and York backed off from the regency.

Henry who had spent so much time placating all possible factions before his catatonia, now with great energy reversed nearly every action Richard of York had taken, including restoring Somerset to power. Stripping Yorkists of their newfound gains and handing them to rival Lancastrians, Henry inconsolably alienated all those aligned with the Yorkist faction.

It was at this moment outright war would begin, if even in a brief glimmer.

In 1455, Henry VI had arranged for a Great Council to meet to decide further on the reassignment of Yorkist holdings. Richard Neville, a Yorkist ally, knowing full well what that meant, assembled a force and marched south. This direct act of insubordination was completely unexpected and Somerset had no time to mobilize royal forces to respond.

At the First Battle of St Albans, the badly outnumbered Lancastrian forces surrounding and protecting Henry VI were compelled to surrender. Somerset and other key Lancastrian heads were killed, and the king entered into his first captivity.

The Yorkists were saavy enough to realize that killing the king would be unsanctioned and trigger harsh reprisals. However as the king was extremely pliable simply telling him what to do would suffice to accomplish all their aims. Henry VI was held in captivity but resumed the throne when he had accepted major concessions to the Yorkist cause, including lining his cabinet with their advisors.

His wife Margaret took up the role of Somerset, though her power had been greatly diminished.

Peace held for three years. There was a new Prince of Wales, Edward of Westminster who Margaret advocated for relentlessly in the dance of power with Yorkists. Furthermore, Henry VI's half-brother Edmund Tudor has passed away, dealing with a local Welsh conflict, though not before fathering a son Henry Tudor with his twelve year old bride.

York himself grew unpopular as many viewed his power hungry politicking with suspicion, not least of all his attempts to marry his own son into the Burgundian line of succession. His own allies were losing ground in their own feuds.

In one of the more comical episodes of this period of history, Henry VI believed that the various factions merely needed to come together in a "Love Day" ritual ceremony of 1458 that included rivals walking arm-in-arm down the street, including having his own wife Queen Margaret paired with Richard of York. Reparations were ordained for various sides, and many words and sermons were spilled on the necessity of peace and love.

In fact, in a time of limited information and coverage, this only served to starkly illustrated who was on which side. Resentment reached a boiling point shortly after this.

The Earl of Warwick had been engaged in naval operations against French allies, and being in command of the English army, was in a strong negotiating position himself. Henry who was still rummaging around to secure a lasting peace with France had decided Warwick was more of a liability than an asset.

Warwick was summarily summoned to come to the throne alongside other Yorkist allies.

Knowing again how this would play out, they refused and assembled their own forces.

Margaret, far more astute than her husband, had on her own initiative began mobilizing royal Lancastrian forces.

After some military bungling on both sides, The Yorkists were pushed back and Richard of York left for Ireland. The new Duke of Somerset was awarded Warwick's post and the Lancastrians gained ascendancy again in English politics.

In 1460, the Yorkist leaders sailed from Ireland to Calais to meet the sympathetic English army there. Commandeering those forces, they crossed the English Channel and marched upon London. London was very sympathetic to York by this point and the doors were virtually thrown open to Richard of York who gained control of England a second time, his allies defeating the Lancastrian forces at Northampton a month later. Henry VI was brought back to London a second time as a captive.

That fall, Richard of York requested that Parliament award him the throne. This was a shocking disturbance not just to Parliament but York's allies. The judges failed to substantiate this claim. He had overplayed his hand. He backtracked to attempt to have the throne merely pass naturally from Henry VI to his own son Edward instead. But this too was too unpalatable for the political establishment.

From this fallout, the Lancastrians experienced a second wind. Jasper Tudor threw in his lot with the Lancastrians, and Margaret successfully procured Scottish support as well. The French threw in their lot with the Lancastrians, to oppose the Burgundian-aligned Yorkists too.

Lancastrians thus sallied forth as 1460 drew to a close, defeating Yorkists and driving Richard of York to Sandal Castle in Wakefield.

In one of those remarkable twists of history, though Richard was outnumbered and safe in his fortress with reinforcements on the way, he made the fatal decision to sortie from the castle and make battle with the besieging forces who clearly outnumbered him. The ensuring slaughter in the Battle of Wakefield led to his death as well as a few of his key allies.

Richard of York's eldest son Edward now became the Duke of York.

In what should have been by all counts a decisive Lancastrian victory became yet again an incisive reverse as Edward's military and charismatic ability led him to rally Yorkist forces and crush the Lancastrians first at the Battle of Mortimer's Cross, killing Owen Tudor in the process.

Queen Margaret still had her own Lancastrian army in the south as did Warwick who still had the king in captivity. While the Lancastrians defeated Warwick at the Second Battle of St. Albans, freeing Henry, Warwick was able to retreat and link up with Edward of York.

Though she had the upper hand, Queen Margaret and Henry VI were in an awkward position. London was in no way inclined to welcome back their decrepit king and simply refused to allow the royal couple to enter.

Hearing this, Edward and the Yorkists rode south to London where they were welcome with jubilation. Riding on this momentum, Edward secured the throne for himself as Edward IV, a title which had evaded his father merely one year before.

No sooner had he been granted the throne (but before he was coronated), Edward IV rode out to quash the Lancastrians. Through several engagements, including the grueling Battle of Towton, Edward established unquestionable control of England. Henry VI, Margaret, and little Edward retreated to Scotland where they would live in exile.

Whatever the questionable means by which Edward IV secured the throne (not perhaps unlike Henry Bolingroke sixty years before), he was certainly a capable administrator and ruler, though given to strong hedonistic impulses. He quite ably balanced the need for clemency over Lancastrian opponents while rewarding his faithful allies such as Warwick.

A short Lancastrian uprising in 1464 was quickly squashed and all Lancastrian military leadership captured and executed. Henry VI too was captured where he was imprisoned in the Tower of London yet again.

Warwick had grown to be the foremost political power outside Edward IV himself, and he leveraged this authority to attempt to control the marriage negotations for the unwed Edward IV. After much vigorous effort, he had arranged for a marriage to the French crown, to cement the de facto peace that had taken root since the English had been kicked out of all neighboring territories. Calais alone remained in English control, surrounded as it was by Burgundy, and unreachable for the French throne.

In yet another new, embarrassing scandal, it was discovered that Edward IV had already been secretly married to minor English nobility: Elizabeth Woodville. The Woodvilles were notoriously ambitious and through such a gambit they entered the national stage as a rival within the Yorkist cause against Warwick.

Warwick was incensed by this development and attempted to wrest all influence from Woodvilles through accusations of witchcraft, though this failed.

In turn, Warwick was blamed for the failure of the French marriage by English and French alike. Warwick's relatives were incrementally stripped of power and titles which Edward repeatedly offered to his in-laws, the Woodvilles.

By 1469, several revolts broke out against Edward IV yet again. Ostensibly as the defender of the House of York, Warwick assembled troops to stamp out insurrection. Instead he hoped to depose Edward IV and installed Edward's younger, more pliable brother Clarence to the throne instead. Royal troops were defeated, many Woodevilles were killed, and Edward himself was captured.

However the subsequent disorder prompted Warwick's proxy rebels to release Edward. The next year, Warwick and Clarence engineered another uprising in the hopes of capturing Edward yet again under better terms. However, Edward IV decisively trounced the rebels, and the captured leader let spill all the secrets of Warwick and Clarence's conspiracy, forcing them to flee in ignominy.

At this point in time, France re-enters the picture. King Louis XI had been snubbed by King Edward IV's secret marriage, and upon receiving Warwick in his court, master-minded a reconciliation between Warwick and Margaret of Anjou who had been cutthroat enemies for years. Warwick's daughter was married to Henry VI's son, and he launched yet another attack against Edward IV before the year was out.

Warwick's brother also joined in from the north, nursing a grudge for being overlooked in his faithfulness to Edward IV.

This coalition far surpassed Edward IV's forces, and so he fled across the channel, and Henry VI was readepted as king, now under the thumb of Warwick in himself.

But of course in another dizzying turn, Edward IV launched his own counter-invasion mere months later in 1471. His younger brother Clarence realizing he was lone Yorkist among Lancastrians swapped sides and Edward quickly took of control of London and King Henry VI yet again.

The rebuffed Lancastrian forces attempted to meet Edward's invading force, but in an embarrassing blunder, started killing their own side in the fog. Edward was triumphant. Warwick was killed alongside his brother.

The Lancastrians were broken. The Neville family (who Warwick belonged to) would never again rise to power.

Margaret landed with a French force to try to salvage the situation, but these too were defeated at the Battle of Tewkesbury, where Henry VI's son little Edward was killed by the men of Edward IV's brother Clarence.

Mere weeks after his son died, the feeble Henry VI passed away in the Tower of London. It is not clear if this was due to natural causes or not, but at forty-nine years, he had lived through far more than most English monarchs though having done much less than any before him.

Margaret herself was also captured. The King of France would pay her ransom but she would die mere years later.

Thus the line of Henry V was extinguished.

The only faintest whiff of blood relative to this line was Henry Tudor, the half-nephew of Henry VI who now lived in exile under the protect of the Duke of Brittany.

It was 1471, and Edward would rule again for twelve more years in relative peace, though his coalition fractured over the decreasing amounts of shared interests they possessed. Never regaining full trust in his brother, and hearing rumors of another revolt, Edward imprisoned and executed Clarence in 1478.

After years of partying and feasting and enjoying the excesses of life, Edward had grown morbidly obese by his early forties and his health was failing. By 1483, his health failed him entirely and his twelve year old son Edward acceded to the throne as Edward V, with Edward IV directing his brother Richard to protect the young boy.

One does not hear much about Edward V.

This is because he was never crowned.

Within mere weeks of inheriting the throne, he would lose it. His uncle Richard sent forces to retrieve him "for his protection". However once he surrendered, he was summarily imprisoned in the Tower of London with his younger brother. Richard established himself as Lord Protector of the realm, and when the two royal boys went missing (for reasons unknown to this day), he wasted no time in having himself crowned as King Richard III.

Richard III would vie with his nominal predecessor Richard II for the sheer unpopularity of his reign paired with his tyranny.

Already tainted with the apparent blood of his nephews who he had been explicitly charged to protect, Richard III had also executed the immensely popular Baron Hastings without even a trial, in spite of the man's undying loyalty to Edward IV. Within quite short order, Richard III effectively alienated his brother's staunchest supporters, including the now powerful Woodeville family.

The trouble is by this point so many Yorkist and Lancastrian contenders had been killed off, there was not much one could do about it.

However, a conspiracy took root. Named Buckingham's Rebellion, it was decided that Henry Tudor should be placed on the throne to rid the realm of Richard III, since Henry was directly descendend from Edward III all those years before.

Buckingham's Rebellion in 1483 was a complete flop. Coastal storms completely rerouted the ships bearing forces and Henry Tudor. Buckingham was found by Richard III and quickly executed.

Richard III then sent request after request to the Duke of Brittany for the extradition of Henry Tudor to London, for his own political security naturally.

While the Duke of Brittany refused such requests, he fell ill and his regent Landais had no issue with complying with the request. Henry VII was bundled up and sent to the coast.

However in the latest twist of history, Henry VII affected illness, so severe that they could not place him on the ship. The delay caused them to miss the tides, pushing out the departure another day.

But in the intervening time, a messenger arrived announcing the regency of Landais had ended and the Duke of Brittany had resumed his rule. Confused as to what should happen next, the delegates bickered among each other. Henry fled to a monastery where he claimed asylum. The envoys respected this right of protection and went away.

From there Henry fled to Paris where he was welcomed.

Assembling a coalition of French, Scottish, and other soldiers, Henry set sail for Wales in 1485, being a Welsh Tudor after all. There he gathered more troops and prepared to march to London before Richard III could drown him in insurmountable odds.

Although starkly outnumbered, Henry Tudor's forces won the Battle of Bosworth Field as several of Richard's allies successively defected as the battle wore on. Richard III himself was killed, and thus the War of the Roses came to an end.

Henry Tudor would reign as Henry VII. The primary Plantagenet line had come to an end. Henry VII honored his deal to marry Edward IV's daughter Elizabeth of York, and the Lancastrian and York lines were fused together in the Tudor red-and-white rose, symbolizing the unity of the two warring families.

It is perhaps most fitting here to end with the story that opens Dan Jones' history of The War of the Roses.

Years after the war had ended, it still breathed its scars.

Henry VIII, son of Henry VII, had arranged for the imprisonment of Lady Margaret Pole, a sixty seven year old woman who had lived her whole life in service to the Tudors. Her misfortune was to be born the niece of Edward IV back in 1473. She was third in line for the throne, at a time when Henry VIII sought with increasing lack of success to father a male heir.

The War of the Roses still stung deep in the English imagination, and even the faintest whiff of pretender, provoked Henry VIII to execute her in a shocking act of tyranny not seen since those bloody days. At 7 AM on May 27th, 1541, she was marched out for public execution.

By Jones' telling, the official executioner was away and so a young man was instructed to perform the decapitation himself. Decapitation is easier said than done, and unfortunately as the sixty-seven year old woman stooped at the chopping block, the young man missed and struck her at an odd angle that caused immeasurable pain. He tried again but failed to kill her, and by all accounts he ended up hacking her head and shoulders to death to put her out of her misery.

It is with such a misfortunate tale that one can say medieval England drew to a close.

The Plantagenets were extinct. Now power lay with the Tudors, and with them, the gateway to modernity.